Trell Got a Baby but He Only 13

How mutual are big babies?

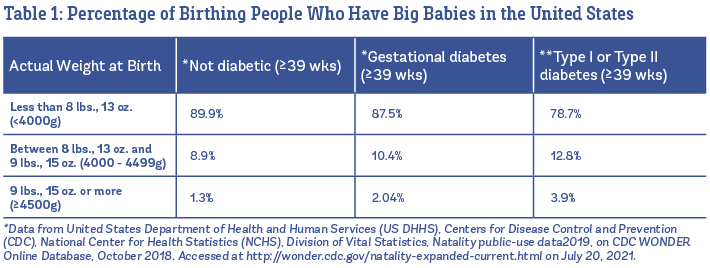

Well-nigh one in ten babies is born large in the United states of america (U.S.). Overall, 8.ix% of all babies born at 39 weeks or after weigh between viii lbs., 13 oz., and 9 lbs., 15 oz., and 1.3% are born weighing 9 lbs., 15 oz. or more (U.Due south. Vital Statistics, 2019). In Table 1, y'all can run across the percentages listed separately babies born to people who are not diabetic, vs. babies built-in to those with gestational diabetes and Type I or Blazon II diabetes.

What factors are linked to having big babies? Big babies run in families (this is influenced by genetics), and it's more mutual to accept a big baby when the baby'southward sexual practice is male person (Araujo Júnior et al. 2017). Equally yous tin can see in Table 1, people with diabetes before or during pregnancy take higher rates of large babies compared to people who are not-diabetic. Other factors that are linked to large babies include having a college body mass alphabetize (BMI) before pregnancy, higher weight proceeds during pregnancy, older age, post term pregnancy, and a history of having a large baby (Araujo Júnior et al. 2017; Rui-Xue et al. 2019; Fang Fang et al. 2019).

Amid people with gestational diabetes, researchers have found that having a higher claret sugar at beginning diagnosis makes you more likely to accept a baby who is large for gestational historic period. (Metzger et al. 2008). However, pregnant people who manage their gestational diabetes through nutrition, exercise, or medication can bring down their chances of having a big infant to normal levels (or about vii%) (Landon et al. 2009).

In addition, there is high quality testify from 15 randomized trials showing that meaning parents who exercise (both those with and without diabetes) have a significant decrease in the compared to those who do not exercise during pregnancy (Davenport et al. 2018).

What is routine treat suspected big babies?

The almost detailed evidence we accept on typical care for big babies comes from the U.Southward. Listening to Mothers Three Survey, which was published in the early on 2010s. Although simply one in ten babies is born large, researchers found that two out of 3 families in the U.S. had an ultrasound at the end of pregnancy to determine their baby'due south size, and i out of three families in the study were told that their babies were also big. In the terminate, the average birth weight of their suspected "big babies" was only 7 lbs., 13 oz. (Declercq, Sakala et al. 2013).

Of the people who were told that their babe was getting big, 2 out of iii said their care provider discussed inducing labor because of the suspected large baby, and 1 out of three said their care provider talked about planning a Cesarean because of the big infant.

Most of the families whose intendance providers talked well-nigh consecration for large baby ended upward being medically induced (67%), and the rest tried to self-induce labor with natural methods (37%). Nearly ane in five survey respondents said they were not offered a selection when it came to consecration—in other words, they were told that they must be induced for their suspected large baby.

When care providers brought up planning a Cesarean for a suspected big babe, one in three families ended up having a planned Cesarean. Ii out of 5 survey respondents said that the discussion was framed as if in that location were no other options—that they must have a Cesarean for their suspected big baby.

In the finish, intendance provider concerns about a suspected big infant were the 4th well-nigh common reason for an induction (making up 16% of all inductions), and the fifth near common reason for a Cesarean (making up 9% of all Cesareans). More than half of all birthing people (57%) believed that an induction was medically necessary if a intendance provider suspects a big infant.

So, in the U.S., most people take an ultrasound at the terminate of pregnancy to gauge the baby's size, and if the baby appears large, their care provider volition usually recommend either an consecration or an elective Cesarean. Is this arroyo evidence-based?

This approach is based on five major assumptions:

- Big babies take a higher risk of their shoulders getting stuck (as well known equally shoulder dystocia).

- Large babies are at higher gamble for other nascence problems.

- We can accurately tell if a baby will be big.

- Consecration keeps the baby from getting whatsoever bigger, which lowers the risk of Cesarean.

- Elective Cesareans for big baby are merely benign; that is, they don't have major risks that could outweigh the benefits.

Assumption #1: Large babies are at higher risk for getting their shoulders stuck (shoulder dystocia).

Reality #one: While information technology is true that 7-fifteen% of big babies have difficulty with the nascence of their shoulders, nigh of these cases are handled by the care provider without any harmful consequences for the babe. Permanent nerve injuries due to stuck shoulders happen in one out of every 555 babies who weigh between 8 lbs., 13 oz. and nine lbs., 15 oz., and one out of every 175 babies who weigh 9 lbs., 15 oz. or greater.

Ane of the master concerns with big babies is shoulder dystocia ("dis toh shah"). Shoulder dystocia is divers as when shoulders are stuck enough that the intendance provider has to accept extra concrete action(s), or maneuvers, to help become the infant out.

In the past, researchers take referred to shoulder dystocia as the "obstetrician's greatest nightmare" (Chauhan 2014). The fear with shoulder dystocia is that it is possible that the baby might not get plenty oxygen if the head is out just the body does not come out soon afterward. At that place is also a run a risk that the babe will experience a permanent nerve injury to the shoulders.

1 of the reasons that intendance providers accept a fearfulness of shoulder dystocia is because if the baby experiences an injury during or after shoulder dystocia, this type of injury is a common crusade of litigation. In a study carried out at the Academy of Michigan, researchers found that half of all parents whose children were being treated for shoulder dystocia-related injuries were pursuing litigation (Domino et al. 2014).

How often does shoulder dystocia occur? Researchers who combined results from ten studies found that shoulder dystocia happened to half-dozen% of babies who weighed more than four,000 grams (eight lbs., 13 oz.) versus 0.6% of those who were not big babies (Beta et al. 2019). When babies weighed more than than 4,500 grams (nine lbs., 15 oz.), 14% experienced shoulder dystocia.

Similarly, i high-quality study that looked separately at significant people with and without diabetes showed that in non-diabetic people, shoulder dystocia happened to 0.65% of babies who weighed less than 8 lbs., 13 oz. (half-dozen.5 cases out of one,000 births), vi.7% of babies who weighed between 8 lbs., 13 oz. and 9 lbs., 15 oz. (threescore out of one,000), and 14.5% of babies who weighed nine lbs., 15 oz. or greater (145 out of 1,000) (Rouse et al. 1996).

Rates of shoulder dystocia were much higher in large babies whose birthing parent had Type I and Type II diabetes (2.ii% of babies that weighed less than viii lbs., 13 oz., thirteen.9% of babies that weighed between eight lb., 13 oz. and nine lb., 15 oz., and 52.v% of babies that weighed more than 9 lb., 15 oz.) (Rouse et al. 1996).

We were not able to find exact numbers for the percentage of people with gestational diabetes who had a baby with shoulder dystocia, as the rates change depending on each person'south blood sugar level. However, in that location is strong bear witness that treatment for gestational diabetes drastically lowers the chance of having a big baby and shoulder dystocia. We cover the bear witness on treatment for gestational diabetes (link evidencebasedbirth.com/inducingGDM) in our Evidence Based Birth® Signature Article on Induction for Gestational Diabetes.

It's interesting to note that people with high claret saccharide levels during pregnancy are at increased risk of shoulder dystocia during birth fifty-fifty when the baby is not large. This is because weight can be distributed differently on a baby when their gestational carrier has high claret sugars. Problems are more likely to occur if the babe'southward head size is relatively pocket-sized compared to the size of its shoulders and belly (Kamana et al. 2015).

Although large babies are at higher risk for shoulder dystocia, at least half of all cases of shoulder dystocia happen in smaller or normal sized babies (Morrison et al. 1992; Nath et al. 2015). This is because overall, there are more small and normal size babies built-in than big babies. In other words, the rate of shoulder dystocia is higher in bigger babies, but the accented numbers are about the aforementioned with bigger and smaller babies. Unfortunately, researchers have found that it is impossible to predict exactly who will take shoulder dystocia and who volition non (Foster et al. 2011).

Considering at least half of shoulder dystocia cases occur in babies that are non big, and we can't predict who will accept a shoulder dystocia, shoulder dystocia will always be a possibility during childbirth. That is, the chance tin only exist eliminated if all babies are born by Cesarean. Because requiring anybody to have a Cesarean is unethical and impractical, it is of import for wellness care providers to train for the possibility of a shoulder dystocia.

Other resources on resolving shoulder dystocia:

- There are means care providers can help prevent and manage a shoulder dystocia. For more than information, read this article on shoulder dystocia by Midwife Thinking.

- Click here for a PowerPoint from a shoulder dystocia training course from the United Kingdom.

- Spinning Babies offers an online continuing education course almost resolving shoulder dystocia. Y'all can also download a free PDF on the FLIP-Flop technique for managing shoulder dystocia here.

- This video and this article describe how care providers tin use a technique called the "shoulder shrug maneuver" to resolve shoulder dystocia (Sancetta et al. 2019).

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has a guideline (last reviewed in 2017) on predicting, preventing, and managing shoulder dystocia here.

Brachial plexus palsy

A shoulder dystocia past itself is non considered a "bad result." Information technology's only a bad effect if an injury occurs forth with the shoulder dystocia (Personal advice, Emilio Chavirez, MD, FACOG, FSMFM). Although well-nigh cases of shoulder dystocia can be safely managed by a care provider during the birth, some can result in a nervus injury in the infant called brachial plexus palsy.

Brachial plexus palsy, which leads to weakness or paralysis of the arm, shoulder, or hand, happens in almost one.iii out of every 1,000 vaginal births in the U.S. and other countries. A baby does not have to take shoulder dystocia to feel a brachial plexus palsy—in fact, 48%-72% of brachial plexus palsy cases happen without shoulder dystocia. When a brachial plexus palsy happens at the same time as shoulder dystocia, however, it is more than likely to stop up in a lawsuit than a brachial plexus palsy that did not occur with a shoulder dystocia (Chauhan et al. 2014).

Although rare, brachial plexus palsy can also happen to babies born by Cesarean. In i study that looked at 387 children who experienced brachial plexus palsy, 92% were built-in vaginally and eight% were born by Cesarean (Chang et al. 2016). Other researchers have constitute that brachial plexus palsy happens in about 3 per ten,000 Cesarean births (Chauhan et al. 2014).

Some infants who have a brachial plexus palsy (most x%-xviii%) will end upward with a permanent injury, defined equally arm or shoulder weakness that persists for more than a year after nativity. It's estimated that there are anywhere from 35,000 to 63,000 people living with permanent brachial plexus injuries in the U.S. (Chauhan et al. 2014). For a blog article almost what it's like to grow up with a brachial plexus palsy, read Nicola's story here.

In 2019, researchers combined five studies about the risks of brachial plexus injury in pregnancies with babies over 8 lbs., xiii oz. versus those with babies who were not big (Beta et al 2019). Big babies had significantly more brachial plexus injury (0.74% versus 0.06%). When babies weighed more 4,500 grams (ix lbs., 15 oz.), the rate went up to 1.nine%.

In a recent study of infants who were all extremely large at birth (>5000 1000, or >11 lbs.), 17 of 120 infants born vaginally had shoulder dystocia, and 3 of those 17 had temporary brachial plexus palsy that healed within six months—for an overall rate of most 1 brachial plexus palsy cases per 40 vaginally-built-in, extremely large babies (Hehir et al. 2015).

In 1996, Rouse et al. published rates of shoulder dystocia and brachial plexus palsy by infant weight. Using the numbers of permanent disability published by Chauhan et al. in 2014, we created a tabular array that helps show the difference between the weight groups.

Importantly, research has shown that when health care professionals undergo almanac inter-professional training (this means doctors, nurses, and midwives training together as a team) on how to handle shoulder dystocia, they tin can lower—and in some cases eliminate—brachial plexus palsy among babies who experience shoulder dystocia (Crofts et al. 2016). Doctors accept been trying to have this successful training (called "PROMPT") from the United kingdom and implement it in the U.S. Results at the University of Kansas showed a decline and then an eventual emptying of permanent cases of brachial plexus palsy with PROMPT annual trainings (Weiner et al. 2015).

To scout a news video nigh the PROMPT training, click here. To visit the PROMPT foundation website, clickhttps://world wide web.promptmaternity.org/.

Can a infant die from shoulder dystocia?

Deaths from shoulder dystocia are possible but rare. In 1996, researchers looked at all the studies so far that had reported the charge per unit of death due to shoulder dystocia. In 15 studies, there were 1,100 cases of shoulder dystocia and no deaths (a death rate of 0%). In two other studies, the rates of infant decease were 1% (one baby out of 101 "died at delivery," possibly due to the shoulder dystocia) and 2.5% (one infant died out of twoscore cases of shoulder dystocia) (Rouse et al. 1996).

In a report published past Hoffman et al. in 2011, researchers looked at 132,098 people who gave birth at term to a alive baby in head- starting time position. About 1.5% of the babies had a shoulder dystocia (two,018 cases), and of those, 101 newborns were injured. Most of the injuries were brachial plexus palsy or collar bone fractures. Out of the 101 injured infants, there were nothing deaths and six cases of brain impairment due to lack of oxygen. With the six encephalon-damaged infants, it took an average of 11 minutes between the birth of the caput and the body.

Assumption #2: Big babies can lead to a higher risk of health problems and complications.

Reality #ii: The gamble of complications with a large infant increases forth a spectrum (lower run a risk at 8 lbs., 13 oz., higher chance at 9 lbs., xv oz., and highest hazard at 11+ lbs.). In improver, the care provider'southward "suspicion" of a big baby carries its own ready of risks.

Unplanned Cesareans

Researchers combined 10 studies (called a meta-analysis) and found that babies with birth weights over iv,000 grams (eight lbs., thirteen oz.) are more probable to take labors that end in Cesarean (Beta et al. 2019). In these studies, the average Cesarean rate was nineteen.3% for large babies versus 11.two% for babies who were not big. When babies weighed more than than four,500 grams (9 lbs., 15 oz.), the Cesarean rate increased to 27%. Every bit we will discuss, a care provider's "suspicion" of a large babe can impact their likelihood of recommending Cesarean during labor.

Perineal Tears

In the meta-assay published by Beta et al. (2019), five studies found a meaning increase in the odds of severe tears with big babies, while 3 studies did not find a divergence. When the researchers combined the results from all eight studies, the overall issue showed that those who give birth to large babies are more likely to accept severe perineal tears, also known as 3rd or fourth caste tears. The risk of a severe tear was one.7% when birthing large babies versus 0.9% for birthing babies who were non big. When babies weighed more than than 4,500 grams (nine lbs., 15 oz.), the charge per unit of astringent tears was 3%.

The largest report (over 350,000 pregnant participants from National Wellness Service hospitals) examined 3rd degree tears and found the rate to be 0.87% with large babies versus 0.45% without (Jolly et al. 2003). In this report, pregnancies with big babies were also more likely to take longer first and second stages of labor and more use of vacuum and forceps. The increase in the use of vacuum and forceps among big babies likely contributed to the increase in severe tears.

The second largest study, which included over 146,000 hospital births in California betwixt 1995 and 1999, found a college rate of 4th caste tears in big babies who were born vaginally (Stotland et al. 2004). Still, quaternary degree tear rates in this study were very high, even among normal weight babies (i.5%), and the authors did not describe how many birthing people had episiotomies, which is a leading crusade of severe tears.

Although having a big baby may exist a gamble factor for severe tears, it may be helpful to compare this chance to other situations that can as well increase the risk of tears. For example, one large study establish that the risk of a astringent tear with a big baby ranged from 0.ii% to 0.6% (Weissmann-Brenner et al. 2012).Other researchers take found that a vacuum delivery increases the take a chance of a astringent tear by 11 times. So, if your baseline risk was 0.two%, information technology would increase to 2.2% with a vacuum, and the utilise of forceps increases the hazard of a severe tear by 39 times (from 0.2% to 7.8%) (Sheiner et al. 2005).

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Researchers combined nine studies that reported on postpartum hemorrhage in people who gave nativity to big babies compared to those who birthed babies who were not big (Beta et al. 2019). They establish a higher rate of hemorrhage with babies over 8 lbs., 13 oz. (4.seven% versus 2.3%). When the nativity weights were over 4,500 grams (ix lbs., 15 oz.), the rate of postpartum hemorrhage was vi%. However, it is not articulate whether this college rate of postpartum hemorrhage is due to the large babies themselves or the inductions and Cesareans that care providers oftentimes recommend for a suspected big baby (Fuchs et al. 2013)—as both these procedures tin can increase the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (Magann et al. 2005).

Newborn complications

Ane study compared 2,766 large babies with the same number of babies with normal birth weights. All babies in the study were born to not-diabetic parents (Linder et al. The researchers establish that big babies were more than likely to have low blood saccharide after nascency (1.2% vs. 0.5%), temporary rapid breathing (also known as "transient tachypnea" or "wet lung," 1.5% vs. 0.5%), loftier temperature (0.6% vs. 0.ane%), and birth trauma (2% vs. 0.7%).

The researchers did not say whether care providers suspected that the babies were big earlier labor began, or if their care was managed differently. More of the big infants in this study were born by Cesarean (33% vs. xv%), which could accept played a role in the higher rates of animate problems, since breathing issues are more common with Cesarean-born babies.

Birth fractures, or broken collar bones or artillery, are rare simply more than likely to occur among big babies. Researchers combined the results from 5 studies and constitute that the charge per unit of nascence fractures among babies over 4,000 grams (8 lbs., 13 oz.) was 0.54% versus 0.08% amongst babies who are not big (Beta et al. 2019). When babies weighed more than 4,500 grams (9 lbs., 15 oz.), the fracture charge per unit was increased to 1.01%.

Stillbirth

Some doctors recommend Cesareans for suspected big babies because they believe there is a college risk of stillbirth.

In 2014, researchers published a report where they looked back in time at 784,576 births that took place in Scotland between the years 1992 and 2008. They included all babies who were born at term or mail service-term (betwixt 37 and 43 weeks). They did not include multiples or any babies who died from built anomalies (Moraitis et al. 2014).

Babies in this study were grouped according to their size for gestational age—quaternary to tenth percentile, 11th to 20th percentile, 21st to 80th percentile (considered the normal group), 81st to 90th percentile, 91st to 97th percentile, and 98th to 100th percentile. The gestational age of each baby was confirmed past ultrasounds that took place in the first one-half of pregnancy.

In this study, in that location were 1,157 stillbirths, and the risk of stillbirth was highest in the groups with the smallest babies (1st to 3rd and 4th to 10th percentiles). The third highest risk of stillbirth death was seen in the babies who were in the 98th to 100th percentiles for weight (extremely large for gestational age). Using the American Academy of Pediatrics growth curve for gestational age, the 98th to 100th percentiles would be roughly equivalent to a baby who is built-in weighing 9 lbs., 15 oz. or greater at 41 weeks.

Meanwhile, the lowest rates of stillbirth were in babies who were in the 91st to 97th percentiles. The increment in stillbirth risk in the largest group (98th to 100th percentile) was partly explained by the birth parent being diabetic; however, there was also a higher run a risk of unexplained stillbirth for babies in the 98th to 100th percentile. Overall, the absolute chance of an extremely big for gestational historic period baby (98th to 100th percentile) experiencing stillbirth between 37 and 43 weeks was most i in 500, compared to i in 1,000 for babies who are in the 91st to 97th percentile.

Another written report on this topic looked back in time at 693,186 births and 3,275 stillbirths between 1992-2009 in Alberta, Canada (Wood and Tang, 2018). They included all babies born at ≥23 weeks only did non include multiples.

This large Canadian database study found several chance factors for stillbirth: giving birth for the first time, having college trunk mass index (BMI), smoking in pregnancy, older historic period, and having medical issues earlier pregnancy such equally high blood pressure level and diabetes. Like the previous report, pocket-sized for gestational historic period was a strong risk cistron for stillbirth. Simply babies who were large for gestational historic period were not at any increased take a chance for stillbirth. In fact, being large for gestational age was protective against stillbirth in the general population.

However, when researchers looked specifically at birth parents with gestational diabetes, beingness large for gestational age was linked with a higher run a risk of stillbirth. The same was true for nascency parents with Type I or Type II diabetes.

The gamble of stillbirth has historically been higher in pregnant people with Type I or Type II diabetes. However, in contempo years the stillbirth rate for those with Type I or Type II diabetes has drastically declined due to improvements in how diabetes is managed during pregnancy (Gabbe et al. 2012). Equally far every bit gestational diabetes goes, the largest report e'er done on gestational diabetes establish no link between gestational diabetes and stillbirth (Metzger et al. 2008). In the Canadian study, gestational diabetes was not linked with a higher gamble of stillbirth unless the babe was also considered to exist large for gestational age.

In 2019, a large study in the U.S. analyzed medical records of stillbirths that occurred betwixt 1982 and 2017. The purpose of this report was to look at the possible relationship betwixt large babies and stillbirth, simply other factors were also considered (Salihu et al. 2014). It is important to note that overall, the rates of stillbirth have declined dramatically in both big and normal-sized babies over the last 4 decades. The reject in stillbirths may exist due to advancements in medical training and pregnancy screening. In this study population, the rate of stillbirth in big babies declined 48.5% (from 2.04 per one,000 to 1.1 per 1000), and it besides declined 57.4% in babies of normal size (from 1.95 per 1,000 to 0.83 per yard).

In total, more than 100 million pregnancies were analyzed in this study. Virtually 10% of the total number of pregnancies were large babies. In the big baby grouping, at that place were 1.2 stillbirths per 1,000 pregnancies, compared to 1.1 stillbirths per 1,000 pregnancies in the normal birth weight range.

The researchers indicate out that the risk of a big babe being stillborn varies from situation to state of affairs, and and then care should be individualized. In other words, not all large babies behave the aforementioned level of potential risk when it comes to the chances of stillbirth. In their study, researchers separated the babies into three groups (grade 1 or 4000-4499 grams, grade 2 or 4500-5000 grams, and grade 3 or over 5000 grams). Babies in the grade three group experienced an 11-fold increase in stillbirth (11 stillbirths per 1,000 pregnancies) when compared to babies in the grade 1 grouping (1 stillbirth per one,000 pregnancies). However, grade 3 big babies fabricated up just i.v% of the total large baby group, while grade 1 large babies made up more than 85% of the total big baby grouping. Overall, the group with the highest risk of stillbirth was the depression birthweight group (14.89 stillbirths per 1,000 pregnancies). The second highest charge per unit of stillbirth was in the grade 3 big baby group. Some strengths of this report are the big data fix and the classification of big babies into grades of macrosomia. A limitation is that because of the manner the data was collected, we don't know if pregnant people who were diagnosed with "diabetes" had gestational diabetes or pre-existing Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes.

Is it Harmful to Suspect a Large Baby?

When a large babe is suspected, families are more likely to experience a alter in how their intendance providers run across and manage labor and birth. This leads to a college Cesarean rate and a college charge per unit of people inaccurately beingness told that labor is taking "also long" or the babe "doesn't fit."

In fact, research has consistently shown that the care provider's perception that a baby is big tin can be more harmful than an actual big baby past itself.

accept all shown that it is the suspicion of a big baby—not big babies themselves—that tin lead to higher induction rates, higher Cesarean rates, and higher diagnoses of stalled labor (Levine et al. 1992; Weeks et al. 1995; Parry et al. 2000; Weiner et al. 2002; Sadeh-Mestechkin et al. 2008; Blackwell et al. 2009; Melamed et al. 2010; Little et al. 2012; Peleg et al. 2015).

In one study, researchers compared what happened when people were suspected of existence pregnant with a big babe (>8 lbs., 13 oz.) versus people who were not suspected of existence pregnant with a big infant—just who concluded up having one (Sadeh-Mestechkin et al. 2008).

The end results were amazing. Birthing people who were suspected of having a large baby (and really ended up having ane) had triple the induction charge per unit, more than triple the Cesarean charge per unit, and a quadrupling of the maternal complexity rate, compared to those who were not suspected of having a large baby only had one anyhow.

Complications were most ofttimes due to Cesareans and included bleeding (hemorrhage), wound infection, wound separation, fever, and need for antibiotics. There were no differences in shoulder dystocia between the ii groups. In other words, when a care provider "suspected" a big baby (every bit compared to not knowing the babe was going to be big), this tripled the Cesarean rates and made mothers more likely to experience complications, without affecting the rate of shoulder dystocia (Sadeh-Mestechkin et al. 2008).

These results were supported by another study published past Peleg et al. in 2015. At their infirmary, physicians had a policy to counsel everyone with suspected big babies (suspected of being eight lbs., thirteen oz. and college, or ≥4,000 grams) about the "risks" of big babies. Elective Cesareans were not encouraged, but they were performed if the family requested i after the discussion. In that location were 238 participants who had suspected large babies (that ended upward truly being big at birth) and were counseled, and 205 participants who had unsuspected big babies (that concluded up existence truly large at nascency) who were not counseled.

Even though the babies were all most the same size, only 52% of participants in the suspected big infant group had a vaginal birth, compared to 91% of participants in the non-suspected large babe group. This increase in Cesarean charge per unit in the suspected big baby group was primarily due to an increase in the families requesting elective Cesareans after the "counseling" session about how big babies are risky to birth. In that location was only ane case of shoulder dystocia in the unsuspected big baby group, and two cases in the suspected big infant group. None of these babies experienced injuries. In that location was no divergence in severe nativity injuries between the two groups.

The authors concluded that obstetricians should not be counseling significant people about the risks of big babies thought to be 8 lbs. 13 oz. or college, considering information technology leads to an increment in the number of unnecessary Cesareans without any benefit to the birthing person or baby. They suggested that researchers should study using a higher weight cut-off (such equally 9 lbs., 15 oz.) to trigger counseling.

Other researchers take establish that when a first-time parent is incorrectly suspected of having a big baby, intendance providers have less patience with labor and are more likely to recommend a Cesarean for stalled labor. In this written report, researchers followed 340 first-time birthing people who were all induced at term. They compared the ultrasound estimate of the baby's weight with the actual birth weight. When the ultrasound incorrectly said the baby was going to weigh more than 15% higher than information technology concluded up weighing at birth, physicians were more than twice as likely to diagnose "stalled labor" and perform a Cesarean for that reason (35%) than if there was no overestimation of weight (13%) (Blackwell et al. 2009b).

Significant people who are plus size and those who take medication for loftier claret saccharide also experience an increase in unplanned Cesareans when ultrasound is used to estimate the infant'due south weight (Dude et al. 2019; Dude et al. 2018).

A contempo study from the U.S. looked at two,826 beginning-time birthing people with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35 kg/gtwo (Dude et al. 2019). Out of everyone in the study, 23% had an ultrasound to gauge the babe's weight within 35 days of birth. The participants who had an ultrasound to estimate the baby's weight were more than probable to have an unplanned Cesarean (generally for "stalled labor") than those without an ultrasound-estimated fetal weight (43% versus 30%). Having an ultrasound to gauge the baby's weight was linked with a higher rate of Cesarean fifty-fifty later considering other factors that could have impacted the Cesarean rate, including the baby'south actual nativity weight.

Amongst the 636 participants who had an ultrasound to estimate the baby's weight, 143 of them were told that their babies were large for gestational age (measuring over the xcth percentile). This grouping had a much higher rate of Cesarean (61% versus 31%). However, only 44% of them (61 out of the 143 birthing people) gave birth to a babe that was big for gestational age.

The authors plant similar results when they looked at around 300 people who were giving birth for the kickoff time and taking medication for loftier blood carbohydrate (Dude et al. 2018). Again, having an ultrasound to approximate the baby's weight within 35 days of birth was linked to a higher rate of unplanned Cesareans (52% for those with an ultrasound versus 27% for those without an ultrasound) even later considering the babe's actual birth weight and other medical factors.

The authors conclude, "Perceived noesis of fetal weight may impact decisions providers brand regarding how likely they feel their patients are to deliver vaginally."

It'due south non surprising that physicians are more probable to plow to Cesarean in these situations, given a cultural fright of big babies. In one medical periodical editorial, an obstetrician with a clear bias towards Cesarean for big babies said that, "Flagging up all cases of predicted fetal macrosomia is vitally important, so that the attendants in the labor suite will recommend Cesarean if at that place is whatsoever filibuster in cervical dilatation or abort of head rotation or descent. Cesarean should also exist the preferred option if an abnormal fetal heart tracing develops" (Campbell, 2014).

So, in summary, although big babies are at higher hazard for some problems, the care provider's perception that there is a big babe carries its own fix of risks. This perception—whether it is true or fake—changes the style the intendance provider behaves and how they talk to families about their ability to birth their infant, which, in turn, increases the chance of Cesarean.

Assumption #iii: We can tell which babies will be large at birth.

Reality #3: Both concrete exams and ultrasounds are every bit bad at predicting whether a baby volition exist big at birth.

Fourth dimension and time again, researchers have establish that it is very hard to predict a babe's size earlier it is born. Although two out of three people giving nascency in the U.Due south. receive an ultrasound at the end of pregnancy (Declercq et al. 2013) to "gauge the infant'southward size," both the intendance provider'due south guess of the baby'south size and ultrasound results are unreliable.

In 2005, researchers looked at all the studies that had ever been done on ultrasound and estimating the baby's weight at the end of pregnancy. They institute fourteen studies that looked at ultrasound and its ability to predict that a baby would weigh more than 8 lbs., 13 oz. Ultrasound was accurate 15% to 79% of the fourth dimension, with nigh studies showing that the accuracy ("post-test probability") was less than 50%. This means that for every ten babies that ultrasound predicts will counterbalance more 8 lbs., xiii oz., five babies will weigh more than than that and the other five will counterbalance less (Chauhan et al. 2005).

Ultrasound was fifty-fifty less accurate at predicting babies who volition be born weighing 9 lbs., 15 oz. or greater. In iii studies that were done, the accuracy of ultrasounds to predict actress-large babies was but 22% to 37%. This means that for every ten babies the ultrasound identified every bit weighing more than 9 lbs., xv oz., merely two to iv babies weighed more than this amount at birth, while the other six to viii babies weighed less (Chauhan et al. 2005).

The researchers found iii studies that looked at the ability of ultrasound to predict big babies in pregnant people with diabetes. The accurateness of these ultrasounds was 44% to 81%, which ways that for every x babies of a diabetic parent who are thought to counterbalance more than eight lbs., 13 oz., around six volition weigh more and four will weigh less. The ultrasound exam probably performs better in diabetics but because diabetics are more likely to have big babies. In other words, it'south easier to predict a big baby in someone who is much more likely to take a big infant to begin with.

Currently, there is no reason to believe that 3-dimensional (3D) ultrasound is any ameliorate at predicting birth weight and large babies than ii-dimensional (2D) ultrasound (Tuuli et al. 2016). Inquiry is ongoing to determine if 3D measurements can be combined with second measurements to better predict macrosomia.

There is also no evidence that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) improves the accuracy of fetal weight estimates. The first prospective clinical written report to compare estimated fetal weight from 2nd ultrasound versus MRI is currently being conducted in Belgium (Kadji et al. 2019). The researchers think that MRI at 36 to 37 weeks of pregnancy could exist much more than accurate than ultrasound at predicting big babies. However, fifty-fifty if MRI is found to be superior, it is very expensive and probably not practical.

Compared to using ultrasound, care providers are simply every bit inaccurate when it comes to using a concrete exam to estimate the size of the baby. However, ultrasound appears to provide more than accurate estimates when pregnant people are plus size (Preyer et al. 2019).

Overall, when a care provider estimates that a baby is going to weigh more than 8 lbs., 13 oz., the accuracy is only 40-53% (Chauhan et al. 2005). This means that out of all the babies that are thought to counterbalance more than 8 lbs., 13 oz., half will weigh more than than viii lbs., 13 oz. and half will counterbalance less.

The care provider's accurateness goes upward if the pregnant person has diabetes or is post-term, once more, probably considering the chance of having a big baby is college among these groups. Unfortunately, all the studies that looked at diabetes and the accuracy of ultrasound lumped people with gestational diabetes and those with Type I or Type Ii diabetes into the same groups, limiting our ability to translate these results.

A systematic review concluded that there is "no articulate consensus with regard to the prenatal identification, prediction, and direction of macrosomia." The authors stated that the master problem with large babies is that it is very hard to diagnose large babies before nativity—information technology's a diagnosis that can only be made later on birth (Rossi et al. 2013).

Even the "all-time" way to predict a large baby is going to have bug identifying actual large babies—near often overestimating the size of the baby. In a 2010 study by Rosati et al., researchers tested different ultrasound "formulas" to effigy out an babe's estimated weight. The best formula for predicting nativity weight was the "Warsof2" formula, which is based solely on the baby'southward abdominal measurement. The results of this formula came inside ±15% of the baby's bodily weight in 98% of cases. As an example, if your baby's actual weight was viii lbs. (3,629 grams), the ultrasound could estimate the baby's weight to exist anywhere between half dozen lbs., 13 oz. (iii,090 grams) and 9 lbs., 3 oz. (4,450 grams).

Many weight estimation formulas accept been published (new 2D and 3D formulas are added every year), and researchers go along to debate whether they are accurate.

Recently, a study compared the "Hart" weight interpretation formula to the "Hadlock" formula (Weiss et al. 2018). The "Hadlock" formula is very popular today and considered by many to exist the virtually accurate (Milner and Arezina, 2018). Weiss et al. constitute that compared to the "Hadlock" formula, the "Hart" formula greatly overestimated fetal weight when babies weighed less than 8 lbs., xiii oz. (four,000 grams) and failed to find very large babies. The authors expressed business organisation that using the "Hart" formula could lead to an increased rate of labor induction and Cesareans, and they ended that it has no place in clinical practise.

Supposition #4: Induction allows the baby to be born at a smaller weight, which helps avoid shoulder dystocia and lowers the risk of Cesarean.

Reality #four: At that place is conflicting evidence about whether consecration for suspected big babies tin can improve health outcomes.

We volition talk about three main pieces of testify in this department:

- A 2016 Cochrane review (when researchers combined multiple randomized trials together)

- The largest study (published in 2015) from the Cochrane review

- The 2d-largest written report (published in 1997) from the Cochrane review

Cochrane Review

In a 2016 Cochrane review, researchers (Boulvain et al. 2016) combined four studies in which ane,190 non-diabetic pregnant people with suspected large babies were randomly assigned (similar flipping a coin) to either ane) induction between 37 and 40 weeks or 2) waiting for spontaneous labor.

When researchers compared the induction grouping to the waiting group, they found a decrease in the rate of shoulder dystocia in the induction group—virtually 41 cases per 1,000 births in the constituent induction grouping, downwards from 68 cases per 1,000 in the waiting group.

They also found a decrease in birth fractures in the elective consecration group (iv per 1,000 vs. 20 per 1,000 in the waiting group). To prevent one fracture, it would be necessary to induce labor in 60 people.

On the other hand, they found an increase in severe perineal tears in the consecration group (26 per i,000 in the consecration grouping vs. 7 per one,000 in the waiting group), likewise every bit an increase in the treatment of jaundice (11% vs. 7%).

On average, babies weighed 178 grams (6 ounces) less when labor was electively induced, compared with those assigned to wait for labor.

There were no differences between groups in rates of Cesarean, instrumental delivery, NICU admissions, brachial plexus palsy, or depression Apgar scores. Three of the 4 studies reported death rates, and there were null deaths in either grouping.

Researchers did not look at patients' satisfaction with their intendance or any long-term wellness results for birthing people or babies.

Largest study in Cochrane review (2015)

The study published by Boulvain et al. 2015 was the largest study in the Cochrane review. In this written report, researchers followed 818 significant people with suspected big babies who were randomly assigned to either a) induce labor between 37 to 38 weeks, or b) expect for labor to start on its own until 41 weeks. This is the largest randomized trial that has ever been done on induction for suspected big babies.

Pregnant people could be in the study if they had a single infant in caput-down position, whose estimated weight was in the 95th percentile (>7 lbs., 11 oz. at 36 weeks, 8 lbs., 3 oz. at 37 weeks, or 8 lbs., x oz. at 38 weeks). Nigh 10% of the participants in this study had gestational diabetes.

There was some cantankerous-over between groups: xi% of participants in the induction group went into labor on their ain, and 28% of participants in the waiting-for-labor grouping were induced.

The researchers institute that meaning people randomly assigned to the induction grouping (whether or not they were actually induced) had fewer cases of shoulder dystocia: 1% of people in the induction group (five out of 407) had true shoulder dystocia compared with 4% (16 out of 411) of those in the expectant management group. None of the babies in either group experienced whatsoever brachial plexus palsy injuries, and collarbone fracture rates were low in both groups (1 to 2%).

The chances of having a spontaneous vaginal nativity was slightly more common in the induction group (59% vs. 52%), merely there was no deviation in the rates of Cesarean and the use of forceps or vacuum. There were no other differences in birth outcomes, including any tears or hemorrhage.

The infants in the induction group were more likely to have jaundice (ix% vs. iii%) and receive phototherapy treatment (eleven% vs. vii%). In that location were no differences in NICU admission rates or whatever other newborn differences between groups.

In summary, this written report found that early on induction (at 37-38 weeks) lowered the rate of shoulder dystocia, just without any accompanying impact on bodily brachial plexus palsy rates, collarbone fractures, or NICU admissions.

The authors suggested that the main reason they found dissimilar results from an earlier randomized trial by Gonen et al. (1997), is because they checked fetal weight earlier and induced babies earlier— between 37 to 39 weeks, instead of waiting until 38 to 39 weeks. This meant that they induced labor when a fetus is large for gestational historic period, but before information technology was technically "big," resulting in the birth of a normally sized baby a few weeks early. For example, in the Gonen et al. written report discussed side by side, significant people were not included in the study until they were at least 38 weeks meaning and their estimated fetal weight reached 8 lbs., 13 oz. Meanwhile, in the newer trail by Boulvain et al., of the 411 infants in the waiting-for-labor grouping, 62% weighed more than 4000 g (8 lbs., 13 oz.) at birth, compared with 31% of those who were induced. This means that the participants who waited for labor to start on its own concluded upward with large babies, while those who were induced early gave nativity before their babies could become large.

The authors of the Boulvain written report recollect that previous studies have not plant a do good to induction because providers waited too long to arbitrate, and they missed their chance for the mother to birth a smaller babe and reduce the chance of shoulder dystocia. Although this approach—inducing labor betwixt 37 and 39 weeks—resulted in lower rates of shoulder dystocia, it also led to higher rates of newborn jaundice, and information technology did not accept any impact on "hard" outcomes such as brachial plexus palsy or NICU access.

Second-largest report in the Cochrane Review

The Gonen et al. (1997) written report was the 2nd-largest study in the Cochrane review (with 273 participants). In this study, pregnant people were included if they were at least 38 weeks, had a suspected big baby (8 lbs., 13 oz. to 9 lbs., fifteen oz.), did not have gestational diabetes, and had not had a previous Cesarean. Less than half the participants were giving birth for the first time. Participants were randomly assigned to either firsthand induction with oxytocin (sometimes also with cervical ripening) or waiting for spontaneous labor.

The results? Participants in the spontaneous labor group went into labor about v days later than those who were immediately induced. Although participants in the spontaneous labor grouping tended to have slightly bigger babies (on boilerplate, 3.five oz. or 99 grams heavier), in that location was no difference in shoulder dystocia or Cesarean rates. All eleven cases of shoulder dystocia, spread beyond both groups, were easily managed without any nervus harm or trauma. Ii infants in the waiting-for-labor group had temporary and mild brachial plexus palsy, merely neither of these two infants had shoulder dystocia. Finally, ultrasound overestimated the baby's weight 70% of the time and under-estimated the infant'due south weight 28% of the time.

In summary, the researchers plant that: 1) ultrasound estimation of weight was inaccurate, 2) shoulder dystocia and nerve injury were unpredictable, and iii) induction for big babe did not decrease the Cesarean charge per unit or the gamble of shoulder dystocia.

Assumption #5: Elective Cesarean for big baby has benefits that outweigh the potential harms.

Reality #5: No researchers have ever carried out a study to decide the effects of elective Cesareans for suspected big babies.

Although some care providers will recommend an induction for a big baby, many skip this step and go direct to recommending an elective Cesarean. Even so, researchers accept estimated that this type of approach is extremely expensive and that it would take thousands of unnecessary Cesareans to foreclose one case of permanent brachial plexus palsy.

In 1996, an important analysis published in the Journal of the American Medical Association proposed that a policy of constituent Cesareans for all suspected big babies was not cost-effective and that there were more potential harms than potential benefits (Rouse et al. 1996).

In this analysis, the researchers calculated the potential effects of three different types of policies:

- No routine ultrasounds to estimate the babies' sizes

- Routine ultrasounds, then elective Cesarean for babies weighing 8 lbs., 13 oz. or more

- Routine ultrasounds, so elective Cesarean for babies weighing ix lbs., fifteen oz. or more than

The researchers looked at the results separately for diabetic and non-diabetic people. Unfortunately, nigh research upwardly to this time signal did not distinguish between Blazon i or Type II diabetes and gestational diabetes. So the term "diabetic" could refer to all three types.

Amid non-diabetics, a policy of elective Cesarean for all suspected big babies over 8 lbs., xiii oz. means that a large number of pregnant people and babies would feel unnecessary surgeries. In lodge to forbid 1 permanent brachial plexus palsy in babies suspected to be over eight lbs., xiii oz., 2,345 people would have unnecessary Cesareans at a cost of $4.9 million dollars per injury prevented (costs were estimated using year 1995 dollars).

With a policy of elective Cesareans for all suspected big babies over ix lbs., 15 oz., even more pregnant people would take surgeries plant to be unnecessary in retrospect, because ultrasounds are even less authentic in higher suspected weight ranges (Chauhan et al. 2005). In order to preclude one permanent brachial plexus palsy in babies suspected to exist over 9 lbs., xv oz., iii,695 people would need to undergo unnecessary Cesareans at a price of $8.7 1000000 per injury prevented.

Such policies would increase rates of known risks from Cesarean, like serious infections, claret clot disorders, postpartum bleeding (hemorrhage) requiring blood transfusions, and newborn animate problems (run into "" from ChildbirthConnection.org).

Amongst diabetics, the results were different—mostly because ultrasound is slightly more reliable at predicting big babies in pregnant people who are diabetic, and considering shoulder dystocia is more mutual in this group as well. If pregnant diabeticswere offered an elective Cesarean for every infant that is suspected of weighing more than eight lbs., 13 oz., it would have 489 unnecessary surgeries to foreclose ane case of permanent nerve damage, at a cost of $930,000 per injury avoided. If diabetics had elective Cesareans when their babies were suspected of being ix lbs., fifteen oz. or greater, it would have 443 unnecessary surgeries to prevent i instance of permanent brachial plexus palsy, at a toll of $880,000 per injury avoided.

Please note: A price-effectiveness analysis is merely equally skilful every bit its assumptions–the numbers that they use to plug into the analysis. For example, how did they determine how frequently shoulder dystocia occurs, the accuracy of ultrasounds, and how many permanent injuries occur? In the Rouse et al. (1996) paper, the authors did a very high-quality literature review to determine these factors. Ane drawback of this analysis is that the costs they reported did not include the toll of lawsuits.

Another important drawback is that this analysis is at present over 20 years onetime.

Since the landmark Rouse et al. newspaper was published, two newer cost-effectiveness analyses have been published. Withal, both of these newer papers had major problems—one of them did not take into account the inaccuracy of ultrasound (Herbst, 2005), and the other researchers had a poor-quality systematic review—using numbers in their assumptions that overestimate the accuracy of ultrasound (Culligan et al. 2005). Because the researchers did not do a proficient chore of making their assumptions, we cannot trust the results of their analyses, and then their results are non included in this Signature Article.

In summary, evidence does not support elective Cesareans for all suspected big babies, specially amongst non-diabetic pregnant people. There take been no randomized, controlled trials testing this intervention for big babies, and no high-quality research studies to run into what happens when this intervention is used on a mass-scale in existent life.

In fact, pregnant people without diabetes may be given 1-sided information past their care providers if elective Cesarean is presented as a completely "safe" or "safer" pick than vaginal birth for a suspected large babe. Although vaginal birth with a big baby carries risks, Cesarean surgery also carries potential harms for the birthing person, infant, and any children born in future pregnancies. It is important to take total data on both options in society to make a decision. To read more about the potential benefits and harms of Cesarean versus vaginal birth, you may want to read: "Vaginal or Cesarean Birth: What is at Stake for Women and Babies?" or the consumer booklet, "What every woman should know about Cesarean Section" from Childbirth Connection.

Guidelines

In 2016, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released an opinion stating that consecration is not recommended for suspected big babies, because induction does not meliorate outcomes for birthing people or babies (recommendation based on "Level B testify = limited or inconsistent bear witness"). The 2016 practise bulletin was reaffirmed past ACOG in 2018. This recommendation is like to their 2002 guidelines that were reaffirmed in 2008 and 2015, and eventually replaced by this new position statement published in 2016. In 2020, ACOG released another practice message stating that more enquiry needs to be done to decide whether the potential benefits of inducing for a suspected big infant to forbid shoulder dystocia before 39 weeks outweigh the risks of early induction (ACOG, 2020).

In 2008, the National Institutes for Health and Clinical Excellence (Nice) in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland also An updated recommendation from Overnice, released equally a draft in May 2021, suggests that all meaning people should be offered induction at 41 weeks, rather than assuasive babies to grow for upwards to 42 weeks, to lower possible complications. This communication is non specific to suspected big babies and is based on expert stance non clinical trials.

French exercise guidelines from 2016 recommend induction for suspected big baby if the cervix is favorable at 39 weeks of pregnancy or more (Sentilhes et al. 2016). This recommendation is based on "professional person consensus," not enquiry evidence.

In all their stance statements since 2002, ACOG has stated that planned Cesarean to prevent shoulder dystocia may be considered for suspected big babies with estimated fetal weights more than than 11 lbs. (5,000 grams) in birthing people without diabetes, and 9 lbs., 15 oz. (iv,500 grams) in birthing people with diabetes.. They land the evidence is "Grade C," meaning this recommendation is based on consensus and expert opinion merely, not inquiry evidence (ACOG 2002; ACOG 2013; ACOG 2016—Reaffirmed French guidelines on elective Cesarean for suspected large babe are consistent with the ACOG recommendation.

Source: https://evidencebasedbirth.com/evidence-for-induction-or-c-section-for-big-baby/

0 Response to "Trell Got a Baby but He Only 13"

Post a Comment